Xi Jinping’s Political Course

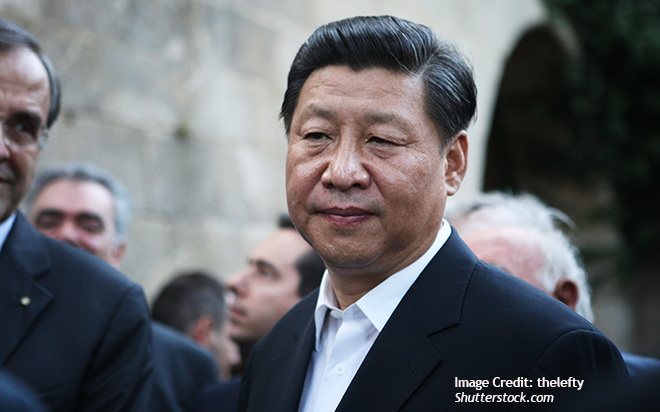

When Xi Jinping became the top leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2012, observers both in and outside China thought of him as a moderate politician well qualified to pursue a political course acceptable to different factions within the Party. He seemed to belong neither to the group with a background in the Communist Youth League, which his predecessor Hu Jintao represented, nor to the strong Shanghai faction that Jiang Zemin had championed, nor to any of several groups within the Liberation Army.

Although he did not clearly belong to any faction, as the son of Party veteran Xi Zhongxun, he was classed as one of the so-called princelings. In 2012 he and Bo Xilai, the son of Bo Yibo, were the most well-known princelings, and of the two the charismatic Bo was more well-known. Xi’s lack of known close ties with any powerful group in the Party led many observers to believe that his rise was the result of administrative competence and an ability to compromise.

Xi’s speeches and writing were cultured and temperate, and his appointment was seen as quite promising. Here was a leader, it seemed, well qualified to navigate in the conflict-ridden waters of high politics in China, and who could steer China in a reasonable direction by means of piecemeal reform.

Tightening Control

No sooner had Xi become the top leader than he began to talk about the demise of the Soviet Union as a warning example for the CCP. He cited this as a reason to tighten Party control over Chinese society, and his own control over the Party. He probably felt what has been called the 70-year Itch.

At first, many advocates of reform believed that Xi was compensating for his lack of a support base and consolidating power to push through reforms in the face of opposition from Party conservatives. In retrospect, this line of reasoning was wrong. Xi has continued to turn away from the direction of Deng Xiaoping’s reform program and instead orienting the CCP backwards in the direction Mao’s China. It is telling that he insists the years 1949 to 1976 laid the basis for rather than retarded the economic growth and modernization of China.

One feature of Deng’s reform program was the delimiting of the sphere controlled by the Party. The government became more independent of the Party. The judicial system developed in the direction of greater autonomy, control over enterprises and industries was loosened, creative entrepreneurs were encouraged and supported. Opening up for trade as well as cultural and educational exchanges was seen as essential to China’s modernization. For the first time since 1949, it became possible to speak about the stifling effects of political control.

Political pundits have long maintained that while China was undergoing unprecedented economic, social and cultural changes, the political system remained unchanged. It is true that that the CCP has remained in control since 1949 and that keeping the CCP in power was a key component of Deng Xiaoping’s political vision. Nevertheless, important changes in the order of governance that took place during the Deng era set the stage for further transformation. One such change was the move away from having one supreme leader with no clearly defined limits to his powers or tenure in favor of a more collective leadership with defined terms of office for top leaders. Another change was allowing local elections in the countryside, which while still controlled by the Party featured unprecedented elements of grass-roots democracy.

All of this, Xi has undone. Collective leadership is no more. Instead, Xi has become the supreme leader with few limitations on his powers much like Mao. Also, just like Mao, he is now having himself portrayed as a great thinker with his own authoritative “thought”.

No room for Dissent

Human rights abuses have been far too common throughout the history of the PRC, but under Xi the situation has further deteriorated. The crackdown in 2015 on some 300 human rights lawyers is just one telling illustration of this. Innumerable people have been arrested and sentenced for exercising what should be their basic freedoms and rights. In Xinjiang the persecution of minorities is so serious that most reputable and independent specialists on human rights agree that what Xi’s policies must be characterized at the least as crimes against humanity, if not genocide. In Hong Kong, the crackdown on the democracy movement not only violates promises about safeguarding existing rights and freedoms, but also involves serious violations of human rights.

The political course during the period between Mao and Xi by no means followed a straight line towards an increasingly open and pluralistic society but rather was characterized by a recurring pattern of alternating phases of “letting go” and “tightening up”, or in more value-laden terms phases of two steps forward and one step back or one step forward and two steps backward. What seems to be new in Xi’s era is that “tightening up” and reversing the course has become a permanent feature of a new dominant model of development. To describe this in more nuanced words, we could say that the transition to a new model became manifest under Xi but that the beginnings of this could already be discerned around 2008 when the Olympic Games took place in Beijing. These Olympic Games were widely perceived as further elevating China’s position in the world and they were used by the regime to promote the sense of national pride in the population.

In any case, there can be no doubt that it was a mistake to believe that Xi initially introduced autocratic measures only to strengthen his ability to embark on the course of reforms he wanted to pursue. We may now clearly see that these measures set the tone for his agenda for decades to come. Xi himself likes to talk about China in 2049, when he envisages that the leaders in Beijing will celebrate the hundredth anniversary of China under the rule of the CCP.

A Totalitarian Future?

The question why Xi has chosen a political course inclining towards totalitarianism is important but difficult to answer. We may assume that it bears the imprint of his personality and reflects some of his deep convictions. Had the Party chosen another leader in 2012, China might well have taken a more reform-oriented course. But Xi’s political course can also be seen in the light of a contradiction inherent in Deng Xiaoping’s modernization program. The purpose of this program was to speed up economic growth and improve the livelihood of the people. But its purpose was also to safeguard the continued rule of the CCP. At the time of Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping and many others felt that unless the Party could deliver more in terms of economic growth and improved standards of living, popular discontent would threaten social stability and the rule of the Party. On the other hand, however, Deng’s modernization policies also threatened the CCP by allowing much more space than earlier for dissent and pluralism.

Thus, from the very beginning in the late 1970s one could argue that the modernization policies increased the popularity of the Party but at the same time meant that the CCP was sawing on the branch it was sitting on. From this perspective the growth of the democracy movement in the 1980s and the repeated subsequent crackdowns on dissent are inherent to Deng’s reforms.

On balance the modernization policies probably led not only to increased economic growth and improved livelihoods but also made the CCP stronger. Nevertheless, the threats to the Party inherent in the modernization program remained, and when Xi became top leader, he opted to eliminate this challenge by expanding the Party’s control over all sectors of society. He was probably also confident that the country’s new economic strength and emergence as a major world power provided an opportunity. Moreover, he could see those problems in the Western world – financial crisis, Trumpism, Brexit, the growth of rightest populism etc. – diminished the attraction of democracy as practiced in the West and would facilitate efforts to strengthen Party rule and make China more authoritarian again.

But will Xi succeed? How far can he go and how long will he and his political program survive? We cannot know. But it would be naïve to assume that there will be a smooth ride for him and his regime to fulfill the goals they have set to reach by 2049 under the continued authoritarian leadership of the Communist Party, goals that involve creating a prosperous, unified and strong country that has incorporated Taiwan under Beijing’s rule. Xi and his regime face several serious challenges, such as climate change and the destruction of the environment, criticism from political opponents as well as new entrepreneurs and capitalists and, last but not least, increasing demands from the population for liberation from the shackles of authoritarian rule.